Exhibitions John Wolseley Heartlands and Headwaters

11.04.15 to 20.09.15

JOHN WOLSELEY HEARTLANDS AND HEADWATERS

NATIONAL GALLERY OF VICTORIA FEDERATION SQUARE

11 April - 20 September 2015

Heartlands and Headlands: the installation

I have taken the wetlands, swamps and rivers of this continent as a starting point for what has become an extended meditation on how water shapes and defines our land. All of these watery elements have formed themselves naturally into an installation that has something of the shape of a great tree, river or human body.

This giant originary tree shape laid out in the gallery has as its trunk The great tree of drawings, which surges through the space. The viewer enters through the Huon pine gateway rubbing, flanked by the southern wetland paintings in the first gallery, and then follows the trunk as it branches out and reaches the northern oceans.

AS TREE FORM. The exhibition starts with its roots in Tasmania, and in the wetter regions of Victoria. Its trunk surges and swells up to the heart of Australia – the interior deserts – and then it opens its arms out to flood plains, deltas and swamps. These fan out into the fretted gulfs and bays of the coasts of Kakadu and Arnhem Land.

AS RIVER FORM. Seen as a river, the exhibition has its headwaters, its source, in the streams and cotton grass swamps of the Tasmanian high plains and moves through the gilgais, lakes and creeks of Gippsland and the Mallee. The waters surge upwards in a number of serpentine loops; the Murray, Darling and Finke rivers move up the continent, and the Daly and Koolatong rivers branch up and lose themselves in the northern seas.

AS THE HUMAN BODY. There is also a human body to be found in the arrangement of the works. The feet are in the mud and button grass swamps of Tasmania and Victoria. The heart is in the Simpson and Tanami deserts. The head is in the rich floodplains of the tropical north. The arteries branch out on either side, through the Lake Eyre Basin into the Channel Country. From the head, like flowing hair, the capillary systems filter through the monsoon rainforests and the mangrove swamps of the coast to lose themselves in the currents of the northern oceans. In Latin, the left hand is caller sinister,and the left hand of this figure rests in the endangered wetlands of the Gwydir River near the Queensland border. It is the hand of industrial man, who by greed and loss of imagination is on the point of destroying his matrix: the water and the earth he needs to sustain life.

The great tree of drawings and Huon pine gateway with pillars

Visitors enter The great tree of drawings through the Huon pine gateway with pillars. One pillar is an ancient tree trunk from Tasmania; another is a vertical slice from the centre of another tree. Both of these wooden sentinels stand as the posts of a gateway entrance.

Near each one is the imprinted image taken from the surface of the wood and transferred onto paper. One is a direct relief print in carbon ink, the other a rubbing done with a graphite stick. The landscape in tree form imprints itself on the paper. The themes of the whole exhibition are encapsulated here, and are part of the larger human dilemma – do we humans listen to and move with the rhythms and dance of the earth and the cosmos, or do we separate ourselves from it and impose structures and systems to contain and control it. The great tree of drawings is my attempt to look at this question from the point of view of someone who draws as a way of thinking. This work is a kind of extended conversation in graphic form about how much the artist imposes ideas on the landscape and how much the artist is a vehicle through which nature reveals itself on that paper. As the poet Paul Celan expressed it: ‘La poésie ne s’impose plus, elle s’expose (Poetry no longer imposes itself, it reveals)’. Many of the systems of drawing you will find on this wall are my efforts to find ways to collaborate with nature and to and receive and listen. I want to narrow the gap between me and the natural forms I am drawing. I feel that is one of the things art can do – a kind of connecting, a kind of mending.

The sequence of these fragments loosely reflects the story of my four years moving up and across the continent. I like to think that I am taking you on that journey as I invent and experiment with all these systems of image making. Each site or type of country seemed to demand a different approach. The groups of drawings are swished along by the watery arabesques of woodcuts of the five river systems I encountered as I travelled.

In the making of this stream of drawings I have stolen the language and script of birds, cicadas, longicorn beetles, and the patterns of seasonal growth rings of trees. I have replicated the tidemarks left on the banks of clay dams, and I have persuaded the roots of trees to draw on my papers. I have found ways of enabling the spawn of coral in tropical seas to fix themselves directly onto the paper. I have left paper to be frayed and nibbled by insects, rotted and decomposed by the myriad living organisms, bacteria and fungal spores.

Often I find that it is through the layering or collision of different systems that I am able to make my own model of a particular landscape. All along the wall I have joined these systems into groups or nests. I describe them as being either collages or assemblages. Collages (from the French coller, to glue) being the term Picasso and Braque coined 100 years ago to describe the early cubist works in which they juxtaposed printed or found materials, newspaper cuttings, fabric and wallpapers to make their paintings. I, too, include works that range all the way from found objects marked by nature in which my hand has had no part, to drawings made in collaboration with natural elements, and works in which I make use of scientific diagrams and impose structures on the landscape in the manner of a magisterial artist. This has all led me to engage in forms of mark making that tend more towards those processes associated with printmaking than painting, from relief printing to frottage.

When assembling all of these passages and bits I found to my surprise that they could almost be seen as a summary of all the modes and processes since the beginning of modernism. A lexicon of all of those technical words, like collage or chiasmage,and also of many of the art movements of our times, the ‘isms’ of the modern movement, from cubism to tachism. For instance: frottage. I take my coloured pencils or a large lump of graphite, and rub it over thin Japanese paper placed over the channels and tracks made by beetle larvae in the wood of trees under the bark of the yellow gums near my studio. I hold up these papers and see that the ‘rubbings’ reveal the life history of a beetle larvae, from egg to grub, and then to the adult beetle as it flies off. And then I discover that it was the surrealist Max Ernst who rubbed his papers over the old scrubbed planks of his studio floor and christened the process frottage.

I have used a variety of processes to make this wall, including decollage,a kind of reverse collage, where instead of the image being built up one cuts into and tears away the image to reveal others underneath. I have used this process to image the way the bark of Manna gums falls away in ribbons in high summer. Crumplage, a state where a drawing has been crumpled and folded, has also been adopted in many of the drawings in this installation that have been blown across the ground by the desert winds. Chiasmage – a diagonal or crossways arrangement where a drawing has been cut in strips and the slices woven together – and sedimentage, my own term for drawings that I have begun to work on and then buried for months or years so that the hidden workings of the earth can continue the drawing, have also been employed. Frots and frotting (from Old English, meaning to stroke or caress) are again my own words, used to describe the process of collaborating with burnt scrub to make drawings. And then there are veilings, grattage, prollage, rollage, transformations, nature printing, intaglio printing, and many more.

Murray-Sunset refugia with 14 ventifacts (2008–10) and Flight of ventifacts, Mallee (2006–12)

carbonized wood, watercolour and graphite on 15 sheets of paper, 120 x 232 cm

The flying papers on the gallery wall are ones I let loose in burnt desert scrub for many weeks, sometimes months, to rise and fall in the desert winds. Each sheet of paper recorded carbon traces in the form of charcoal, stipples, grazes and marks, made by the burnt fingers of the trees and shrubs. When I returned to collect them I usually found they had travelled long distances; often held in the arms of trees or nestled in banks of sand. Having been made soft from dews and showers, and dried and tossed by the wind, they had become fixed in a variety of sculptural forms.

The first section of works, Murray-Sunset refugia with 14 ventifacts, documents this activity and tracks the movement of several of these ‘ventifacts’.

Through this flight of paper ventifacts I have drawn an enlarged version of one of the most significant scientific diagrams of our time: the Keeling Curve, made at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii, which plots the rise in CO2 in the atmosphere from 1958 to the present. I have juxtaposed a sharply rising line on the gallery wall, with the rise and fall of my wandering ventifacts. The progression of this graph up the wall dances up and down in a zigzag motion, as each year the CO2 rises and falls in response to the leaf cover of the deciduous forests in the Northern Hemisphere. Each year in the north, when summer turns to winter, the CO2 increases as the leaves disappear and the level of photosynthesis falls. The CO2 decreases again in the spring with the return of the green foliage. Here, stolen from science, is a wonderful image of a breathing earth. There is a steady movement upwards, and the graph line hits the top of this wall about now, having reached 400 ppm this year (2015). The CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, with its linkage to rising temperature, is near the highest it has been for the last 400,000 years. We are reaching a point of no return.

The paintings

My paintings often have their origins in a special experience – a moment in time in wild country when the land reveals something of its secrets – an instant of seeing into the life of things.

Many of us have these experiences, and as an artist I am lucky to have a way I can celebrate them. In a way I think it’s true that this is one of the special things artists can do – have these moments of vision and then reveal the inner nature and hidden forms of the earth by making things.

For me it’s around these times that the life of a particular place reveals itself – that nature which ‘loves to hide’ as Heraclitus said. And so there I am, staring at a particular bird, or the patterns of reeds moving in the wind, or a fish glimpsed in the pool of a stream. I am looking at the pulse, the energy, the flow of the earth – what the early Greeks called phusis – and by an act of what they called poiesis I make images of it, which turn it into something else: a bit of art.

These paintings are a distillation of those moments in time – sometimes epiphanies, sometimes sensings of unease or foreboding, sometimes wonder at the sheer power and beauty of nature.

In the notes about each painting in this catalogue, and as panels next to the paintings, I have tried to describe in words the emotional nature, the mood of that initial experience, as it follows through to the making of the work.

Wordsworth defined poetry as ‘emotion recollected in tranquillity’. Each of these paintings was started out in the bush, and then continued in my studio as a recollection of its inception. In a mysterious way I find that the mood or feeling of each work carries something of the way in which mood is associated with the different keys in musical composition. For instance, the painting of spiny-cheeked honeyeaters is definitely in D major, the key linked to feelings of triumph and jubilation. While the feeling of the painting Dystopia – the last wetland, has fallen into the key of D minor and has a sense of existential angst or cosmic distress.

It is fitting that the visitor to the exhibition is led to the northern reaches of the continent, to the edge of the great flood plains of Garrangari and Garangalli. It is here over the last few years that I have become aware of the limits of my own western traditions of science and art. Under the tutelage of Mulkun Wirrpanda and other Yolngu elders I am just beginning to find new ways of connecting with the earth. As the surrealist poet Paul Éluard put it, ‘There is another world and it is in this one’.

Natural history of a sphagnum bog, Lake Ina, Tasmania 2013

watercolour on eight sheets 140 x 400cm

As a creek moves down to the shores of Lake Ina in the central highlands of Tasmania, it swells out into an ancient sphagnum moss swamp. I leant over and peered into a gap between the mats of sphagnum, and a small fish emerged in the crystal water. Sun and shadow filtered through the branches of the trees above, pulsing on the dapples and stipples on its tiny, scaled body. Then it was gone.

This brief phantom – this Clarence galaxias – was only miraculously there because its ancestors had been isolated by a glacial moraine upstream, which 6 million years later had saved it from the European trout, which had supplanted all the other galaxias in the rest of Tasmania. And then marvellously it had been saved again by a group of conservationists who purchased these plains and subsequently made them into a protected area.

As the grey shadows moved down the hill and melted into the lake, I soaked and painted the spongy sphagnum mats with tinctures of watercolour – viridian and crimson and Indian yellow – and laid them on several sheets of paper. I did the same with water milfoils, spike reed, tassel sedges and a bladderwort with Tyrian purple petals. I then weighted them down overnight with slabs of bark so that the paper would have their images imprinted on them. Later, as a thin finger of moon illuminated these little bark dwellings, I pictured the images of the swamp slowly emerging under them like a photo being developed, or the traces of a figure on a shroud.

I looked again into the dark pools between the constellations of moss, and there was reflected the whole Milky Way galaxy. I knew that little galaxias was still there, too, suspended in the stars above the countless pavilions of moss deep in the earth. Then I understood why this Clarence galaxias,this little sliver of stardust, shared its name with the galaxy in which it rested.

Key of C minor. Sense of fragility and the ephemeral. Lacrimae rerum – the tears of things.

A natural history of swamps III, heron in swamp – Loy Yang Power Station (2009–10)

watercolour on paper , 114 × 176cm

In 1978 a black-backed heron would often fish in a little dam near the ruined farmhouse in the Strzelecki hills in Gippsland where I was living – my first home in Australia. Some thirty-five years later I was looking at a little dam in the grounds of the Loy Yang Power Station not far away from that shack, and in flew an identical heron. It looked for fish in the water and then peered at a billboard on which was written ‘Hazelwood Power Station – WETLAND DEVELOPEMENT PROJECT’. I walked down to the vast open-cut coalmine below, and looked for fish fossils and Cryptogamic flora among the seams of coal. Then I returned to the heron, which now seemed to be looking at the steam and CO2 that was belching out of the Loy Yang cooling towers – those clouds of CO2 that came from the coal which was once a carboniferous swamp. I looked at the heron and drew it. It looked at me and then flew off in the direction of the Strzelecki hills. I drove off to Melbourne wondering what it all meant.

Key of F-sharp minor. Confliction.

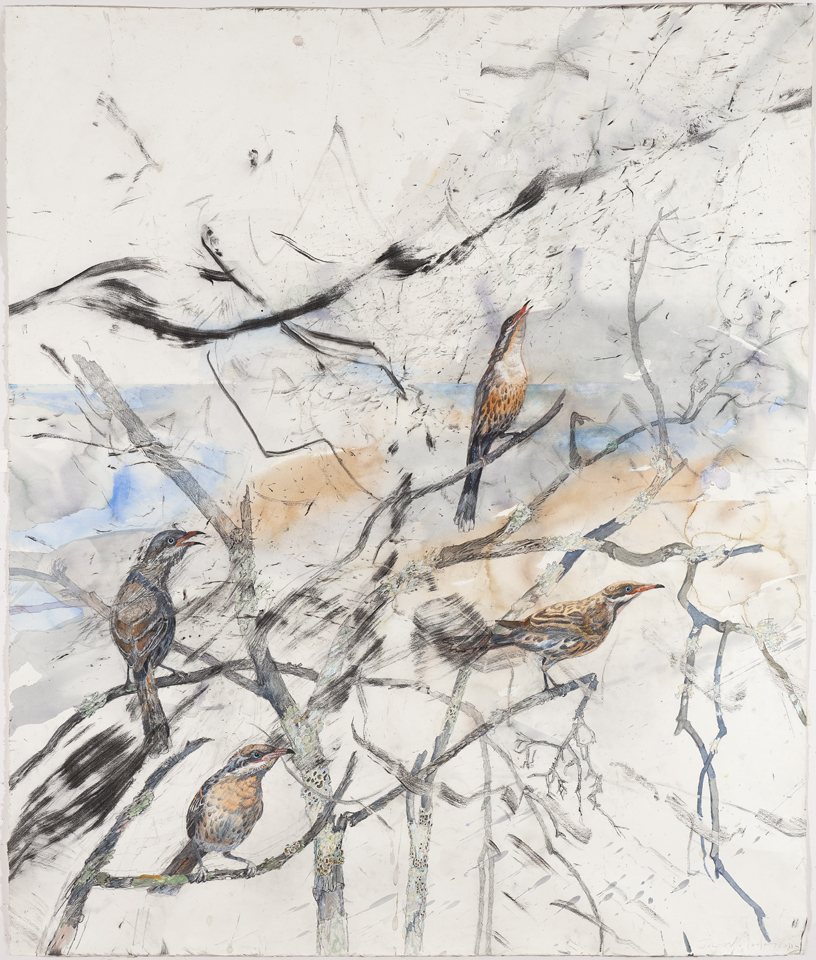

After fire – spiny-cheeked honeyeaters at Lake Monebeong (2009–11)

watercolour, charcoal and graphite on paper, 150 x 128cm

Early one morning I walked down through the Cobboboonee Forest in Victoria and, skirting the dark skeletons of a recent bushfire, I reached a lake where fresh water had come to rest in sand dunes bordering the sea. I stood beside a burnt banksia tree with powdery black, corrugated bark. Embers still glowed deep within it and a thin plume of resinous smoke rose into the air. It had been a stormy night, but now the sea was calm, with only an occasional murmur as a lazy wave unfolded on the sand. The lake, too, was calm and above it rested a layer of mist like a horizontal veil.

Several spiny-cheeked honeyeaters swooped down from the forest, perched in the branches of the tree and sung out fiercely and jubilantly. It was as if they were filled with elation at all these elements coming to rest in equilibrium – the lake resting within the sand dune, the dying down of the wind and the passing of the inferno of fire.

Key of D major. Jubilation. Triumph.

History of the Whipstick Forest with ephemeral swamps and gold bearing reefs 2011

watercolour, charcoal and graphite on paper 234 x 287cm

One day in early summer I walked from my studio into the forest, and followed a dry creek up to some swamps and pools bursting with life – tiny indigo dragonflies, white-naped honeyeaters, and a host of flowers and sedges. This arid landscape, so battered, torn up and churned over, was still miraculously reinventing itself. Such resilience!

I made a drawing that I later added to this large composite work, which brings together the histories of three kinds of time: the ‘deep time’ of geology, ‘shallow time’ since European arrival, and ‘now time’ in October 2011.

The history of the hidden workings of the earth I stole from an old map that describes the folding and unfolding of strata, and the reefs of igneous rock in which the seams of gold grow. This map moves up to the centre of the painting and there, resting on this ancient framework, a green swamp and creek swells and flows as I draw it. As I was painting this I thought of another visitor to this forest, some 160 years ago, William Johnson. His adventures are described by William Sandbach on his map of early Bendigo, which I have redrawn on the top of my painting:

About middle of October 1851, William Johnson a Sydney native, then about 24, stopped a night at the Bendigo hut, and going out with the shepherd in the morning ... picked up a bit of slate with a spec of gold in it. Showing it to the shepherd Ben Hall he said: ‘Is this gold?’ Ben let it fall and they walked on, Johnson to the Bullock creek, and Ben to afterwards root about and find more gold. The finding of that gold was the birth of Bendigo as a goldfield.

When I was working on this painting, this bit of bush with its creek was burnt in a ‘planned burn’, as part of the state government’s legislation to burn every bit of public bushland in Victoriaevery few years. This kills the fire-sensitive plants in this type of bush; there is not enough time between burns for new plants to mature and seed. As I continued on with the painting about the resilience of nature, my mood moved from reverence for that resilience, to a sense of deep chagrin that yet again we were destroying the matrix which is our home.

Keys of G major and A-flat minor. Resilience. Chagrin.

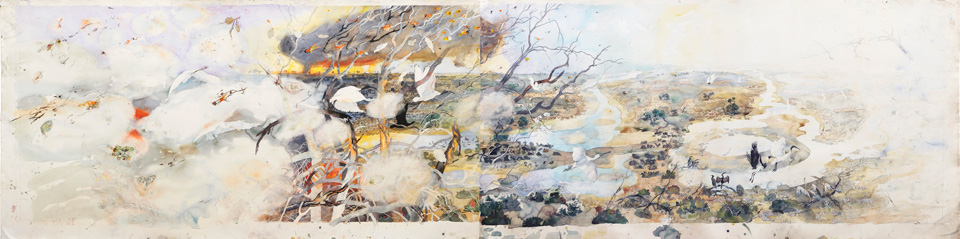

Cycles of fire and water – Lake Tyrrell, Victoria (2011–12)

watercolour, charcoal and graphite on paper 150 x 600 cm

I was sitting on a low sandbank and drawing the pools of water that lay on this ancient salt lake. A warm wind came up and I noticed on the horizon a rust-coloured cloud erupting into the air and darkening the sky over the lake. The pulse of the wind grew stronger, as if emanating from the core of the fire, and it carried embers and burning branches like dismembered limbs. I felt a kind of disquiet, almost of dread. I knew how such a fire has always been part of the natural cycles of the bush but this was one of several I had experienced that season; it felt as if fire itself was behaving in a different, more erratic way. It was as if the patterns of fire behaviour were changing.

Fires had been self-igniting more often in strange ways, or country had been deliberately burnt too frequently – leaving no time for mature trees to have seeds or for the regrowth of burnt stumps.

From out of the churning and billowing clouds of smoke and steam some spoonbills, ibis and cormorants emerged, and flew far out over the lake. Several of them alighted on a patch of sunlit water and remained there, as if illustrating some cycle of eternal return – from action to stillness, from noise to quiet. But as I watched them, the great black cloud drifted over their resting place, moving them on as if they were prematurely being chased away from the world they had known.

Key of F minor. Sense of transition.

Mallee ‘gilgai’ – ephemeral pools, Wyperfeld National Park (2009–12)

watercolour, charcoal and graphite on paper 150 x 107cm

One summer I was camped at Round Swamp in the Wyperfeld National Park. Surrounded by sandhill country, this low-lying clay pan has various crab holes, or ‘gilgai’, which appear from time to time. Over a few weeks I watched from the shade of a gnarled bull mallee as one such pool slowly filled a shallow dip in the ground and attracted a host of frogs, dragonflies and honeyeaters. After enough time to enable some tadpoles to grow legs the water slowly lessened to become a foot-wide puddle, a kind of fish soup. And then under a full moon, over a period of an hour or two, I watched from my tent as the gilgai filled up again. It was as if some secret tide had pulled the water from deep within the earth.

In fact these pools appear in response to invisible flows beneath the clay surface as the ground water in hidden aquifers rises and falls. As I painted this mysterious waterhole I found that more than ever before this process of making a watercolour seemed to be analogous to the action and process by which water itself moves and forms the landscape. I laid out huge sheets of paper on the banks of sandhills and started in a rather wild and physical way by pouring, brushing and sploshing quantities of watercolour that I had previously mixed up in large bowls. All those watery landscape elements around me were then recreated on the paper. Pools in depressions on the paper overflowed in slow, winding rivulets and became an analogue of what hydrologists call ‘chain-of-ponds systems’.

These dried over several hours, and spidery reticulations appeared – the contoured watermarks left by the slowly evaporating liquid. As the sun dried them, the pigments suspended in the pools of colour thickened and sometimes caked and cracked – the way mud does in a drying water pool.

Key of B minor. Sense of intimate immensity.

Regeneration after fire – the seeders and the sprouters, Mallee 2009–11

watercolour, charcoal and graphite on paper 154 x 256

I went for a long walk, deep into the Big Desert Wilderness Park, through waves of mallee scrub, broken at times by little islands of Parilla sandstone rocks that stretched to the horizon. The wind swept the mallee trees this way and that – their leaves a glittering sea one moment and then hanging calmly like blue-green glass the next. It was as if the country still held a memory of the times when this desert was a Cambrian ocean bed on the ancient continent of Gondwana.

I reached one of the outcrops and looked down on the large dome of a mallee fowl’s nest and around it, scattered at intervals, were what appeared to be rocks. Some of the lumps were in fact mallee roots, which had assumed an almost geological appearance. Others, recently scorched by fire, had amber, scarlet and mauve curling around them as vivid new growth exploded from the surviving stump. Nearby, segments of weathered sandstone had fallen from the outcrop on which I was sitting; these were surrounded by scatterings of tiny, bright banksia seedlings. The fire had caused the knobbly seed pods to burst open and expel their seeds. Botanists call trees that react this way to fire ‘seeders’, while their companions, the mallee eucalypts, are known as ‘sprouters’. Sprouters have a large root, known as a lignotuber, which stores water and nutrients in its fibrous interior. These mallee roots are part of a brilliant strategy for survival. After fire or long periods of drought, these hidden aquifers enable the plant to secure its future by sending out a spray of young foliage that will join the newly germinated seedlings, and the mallee scrub will surge again over the sandhills.

Key of A major. Hope.

Ephemeral water with new growth – Murray-Sunset National Park (2009–12)

watercolour, charcoal and graphite on paper with 4 ventifacts 230 x 325 cm

After periods of rain in the Murray-Sunset National Park, I always marvel at how, in just a few hours, seedlings appear in the swales and dips of these sandhills. The emergence of new life after rain, on what was once a desert of dust and dryness, is an experience of great power. These are one of those moments of ‘astonishment of being’ that seem to come to one particularly in deserts. It is the ultimate mystery: ‘Why is there something when there could be nothing?’

Here in the swale between two sand dunes was a piece of ground where a recent bushfire had caused the trees to cast their seeds onto the sand and the rains that followed had allowed them to germinate.

This work joins together two strands of my painting practice. The first is about more objective methods of drawing the ground as I look down on it, in this case depicting the ephemeral water pools and the patterns of the seedlings as they burst out of the sand. The second strand comes about from my exasperation that this objective approach somehow compounds the strong sense I have of a separation and distance from the flow of nature, reflecting the homelessness of our modern condition. This dissatisfaction led to a number of drawing approaches that involve tactile contact with the trees, collaborating with them in making a drawing. In this work the large sheet of paper was moved and rubbed against the burnt trees, while the free-flying sheets of paper had spent much longer being blown by the wind, and being drawn on by the carbonised fingers of the burnt scrub. During that time there had been another movement down the swales – that miraculous mist of tiny green leaves lightly dusting the dunes.

Key of E major. Astonishment of being.

Dystopia – the last wetland, Gwydir 2184 (2012–15)

watercolour, feathers, charcoal, graphite on paper 280 x 610

I found a dead pelican lying on the edge of a vast cotton farm near Moree in regional New South Wales. The once rich, fertile land had been lasered, and flat fields of cotton now stretched as far as the eye could see. Once there were wetlands there, but they had been replaced by an industrial monoculture that would result in the kind of degradation of land and water resources, and loss of species, which is happening in so much of our continent.

It was a poignant moment. I looked at the skeletal bird in the water and thought of drowning Icarus with his broken wings, lying in Bruegel’s famous painting. I remembered how Icarus had come to grief through his over-ambition and his fascination with fire. And now we modern Icaruses, with our addiction to the firing of fossil earths to make energy, are probably causing our own death and extinction.

I made this painting by flinging inked-up, dead carcases of pelicans, owls and bustards onto the paper. Their imprints lie there on this painting, below an image of the Gwydir Wetlands – one of a shrinking number of wetlands in New South Wales, and home to thousands of water birds and rare plants. Around this last wetland I then drew the tabula rasa of the invading cotton farms.

In this painting I have imagined how things might go for the land – and how this wetland in the future, say 2184, might be the last one left. The terrible spectre of DESERTIFICATION now stalks us. Until we change our current land-use practices and our reliance on fossil fuels. Until we change our ways.

This painting has within it the memory of one person who did show a different way. Central to the Gwydir region was a large farm owned by a brilliant farmer who had conserved the wetlands and ran stock as well as crops, all in a sustainable and commercially successful way, for thirty years. When he wanted to retire, rather than selling his land to the cotton barons he accepted a lower price so that it could be bought by the state. It is now part of the Gwydir Wetlands State Conservation Area, and the vast number of waterbirds and rich ecosystems are saved for posterity.

Key of D minor. Dread. Anxiety. Cosmic distress.

Saline grounds, S.A. (2013–14)

watercolour, carbonized wood, oil paint, graphite on paper 123.5 x 355cm

Lying in my swag on saline ground, I woke at dawn to see long shadows creep along the sand and disappear behind an old wire fence. Cold dampness gave way to the benign warmth of the sun. I lay my hand on the salty sand and sensed beneath it the uncanny presence of the invisible salt being pulled up from its hidden geographies to smother the surface of the earth.

I made this work about a patch of ground in a part of the country where large areas of once fertile ground have been cleared of trees, the water table has risen and the salt has killed the remnant vegetation. In Saline grounds I have beguiled the flows and pools of watercolour to make them mimic the subtle way salt works – its fluid movements and encrusted reticulations. To contrast with the mercurial fluidity of the salt I have drawn a calligraphy of fencing, a linear progression that was once a firm boundary between paddocks but is now fraying and becoming loose. At intervals the wire is springing free of its attachments and curving out as if to join up with the more rounded lines of the saltpans. The actions of wind, water and salt are playing their entropic game on humankind’s linear thinking.

In many of the works in this wetland series my passages of dry drawing inscribed by burnt scrub weave in and out of the more Dionysian flowing of my watercolour paint. In this painting the mysterious, cancerous presence of salt infiltrates and draws them together.

Key of C-sharp minor. Sense of danger and alienation.

Flight of the eumenine wasps – mud domes and paper nests (2012–14)

watercolour, ceramic, found ochres on paper, 114 x 466 cm

In the heat of summer I often pin up my sheets of drawing paper by a large open window overlooking a big brown dam. On waves of cool air coming in from the water, two kinds of eumenine wasp career into the studio, searching for places to build their nests. Paper wasps attach their honeycomb discs to the ceiling, and the potter or mud dauber wasps build their little stacks of clay pots on the walls of the studio.

The wasps work away at their structures of mud and paper while I scribble and draw on my scraps of paper on the wall. Their little buildings start to grow, enclosed by my studio – another kind of building that had also slowly grown over time, made with mud, concrete and gravel.

One day I laid my paper on the bank of the dam. With a large brush made of cockerel feathers I let watercolour and clay run down the paper and fan out to form small pools or dams on the page. When dry, I hung it up on my studio wall. There were spidery reticulations – tidemarks – whose bands and contours mimicked in microcosm the same processes of drying as those that could be seen on the tidemarks on the banks of the dam itself. I stood there by the window, musing on this, when one of the mason or potter wasps brushed past my face, performed a complicated dance around the studio, and then deposited a small daub of clay in the centre of one of my dried pools on the painting. She then went back and forth, slowly building it up into a nest. While she was busy doing her artwork I made my own drawing of one of the paper wasps’ nests on the left side of the paper. Later I took the mud dauber nest down the road to a human potter. The clay dwelling of the potter wasp was fired by her in a kiln, and it was then attached to the paper on the same patch on my drawing where it had first been made.

It felt rather eerie, and yet oddly reassuring, as if some beautiful map of the lived world of this little insect had been gently transposed onto a map of my own ‘life world’. There, in the image of that mud nest was a point of meeting where our lives touched. We were both making things out of mud. We were both moving with the nature and being of water and clay, alternating liquid and dry states in cycles of eternal return. We were also trying in some way to transcend our brief lives: the wasp to make a dwelling in order to rear its children and continue its lineage; the human to make that same dwelling more permanent by turning it into an earthenware pot. The human artist thinking in his vain way that he will leave something which may continue to live long after he has returned to the clay from which he came.

Key of G major. Feeling at home in the world. Sense of the oneness of all things.

Simpson Desert sand dunes moving across the Finke River, S.A. 2014–15

watercolour, carbonized wood, graphite, oil paint on paper 320 x 345 cm

In July 1990 I travelled with Brownie Doolan to visit his ancestral lands deep in the Simpson Desert. Brownie was a man of mischievous charm and huge knowledge, and the very last speaker of Lower Arrernte – the language of that region of the Simpson Desert. We drove south across thousands of sand dunes and camped above the Finke River. We ate looking across the deep gulch the ancient river had cut into the sand plains. A grasshopper landed on my knee. Brownie said its name – ‘ngarr ngarr’ – in a soft voice, and I thought that is probably, after thousands of years, the last time this word will hang in the desert air. The grasshopper then flew off in the same direction as the blowing sand of a slow-moving dune, which having reached the edge of the river continued on the opposite bank as if the vast riverbed was hardly there.

In 2013 I was flown in a helicopter over the same stretch of river. I did a drawing from that bird’s-eye view and later worked on this painting with the memory of that evening spent with Brownie often in my mind. I painted the sinuous sand dunes as they flow into the distance as far the eye can see. Changes in wind direction can make these snakes of sand merge or fork out to form compound dunes. I love the way they seem to be giant, abstract demonstrations of the primary or originary shapes in nature. Here the dunes are a living embodiment of the idea of ‘matter as potential’. Each linear dune as it travels onward seems about to morph into some other shape – a crescent dune or one of those parabolic dunes with convex noses trailing elongated arms. The dunes in this painting are mostly seriously committed to heading north, but always with the possibility of branching off to the east under the influence of the prevailing winds. Thus they form one of the most primal forms in nature: the branch that forks, with one line of growth turning into two, then three, four and more, as can be seen in the plants growing on the sandy foreground of this painting. They are acting out in microcosm the same branching shapes as the giant versions blowing across the vast desert beyond. One of the plants is a purslane (Portulaca oleraca) an important food source for the Arrernte people. When its stems turn from green to red it throws out clouds of seeds, and then the spent plant turns black. This was explained to me by my friend, the ethnobotanist Peter Latz, who pointed out that it is described in these parts in a ritual song recorded in Songs of the Aranda, translated by T.J.H. Strehlow:

The forks of the lijua plants are reddening with the seed;

The forks of the ljaua plants are casting down their seed.

…

From the hard ground (the forks of the ljaua plants are rising upwards again).

May the seed turn black as the night!

May (the light of) the sky scorch black the forks of the plants!

Key of G minor. A sense of infinity.

From Siberia to Roebuck Bay – the godwits reach the mangrove swamps, W.A. 2012

watercolour on paper 152 x 200 cm

Each year in June wading birds like the bar-tailed godwit fly 12,000 kilometres from their breeding grounds in Siberia all the way to the north coast of Australia. I was standing on the edge of the sea on the north Kimberley coast when out of a clear sky the godwits arrived.

There was a distant blur on the horizon, and then vast, pulsing flocks of these waders filled the whole sky and swooped down in waves to rest on the mudflats between the mangroves.

The body of the land, its mudflats and sandbanks, had been pushed and pulled by the great king tides, dragged for eons by the cycles of the moon. And now I could see these great tides of godwit, pulled by another powerful force, flow down and merge with the moving waters, rise up again and, with a slow fall, see the individual particles float down to the ground and become birds.

Key of F-sharp major. Arrival. Resolution. Relief after struggle.

A Daly River Creek, N.T. 2012

watercolour, pastel, woodcut and linocut on paper 150 x 600 cm

Here is a flowing tropical creek somewhere near Nauiyu, about two hours’ drive south of Darwin. It shows the fecund flowing mass of life and aquatic plants and fish, and how they are all an integral part of one particular ecosystem. The plants were all drawn on the spot or collected and drawn later in Darwin. It was May 2012 when I went on several trips with the ethnobiologist Glenn Wightman, the Ngan’gi elder Patricia Marrfurra McTaggart AM, and other artists from the arts centre at Nauiyu. They were doing the last research for the book the Ngan’gi Plants and Animals (2014).

They showed me the plants in their living habitat so that I could draw them in action, rather than as dried museum specimens. I began to understand the extraordinary, long, convulsive stems of the Nymphaea waterlily, which are shown in the middle of this painting, and how the plant can expand its stem outwards and upwards for several metres in flood times, and then recoil them as the water recedes in The Dry. Swimming within the flow of the painting here are also several species of bladderwort. The leaves of this carnivorous plant have evolved so that they have become a network of freestanding veins with little traps attached to them, which ‘eat’ small organisms like rotifer and diatoms. By getting their nutrients this way the plants have dispensed with the need for roots. Among these plants I have also drawn water chestnuts (Eleocharis sphacelata); Triglochin dubium (Wandan in Ngan’gi language); duckweed (Lemnaceae); two different species of Nymphaea lily (hastifolia and violacea); and one Nymphoides lily (Aurantiaca). Within the stems of the Nymphaea lilies lurk archerfish, waiting to shoot their jets of water at unsuspecting insects resting on the foliage above the water.

In these tropical aquatic paintings I have tried to show how landscape for me is made up of energy fields rendered as passages of particular plant forms, in which the individual plants move or dance with different rhythms. My intention is to show how these rafts of different species weave in and out of one another, and across the surface of my painting, rather as a passage of a symphony changes key and mood.

I see these as being rather like passages of writing where the individual plant shapes are like letters or calligraphy. Taken individually, each plant has evolved its particular dynamic form to live in the medium of water so that the areas of Monochoria species, for example, constitute an energy field of ‘Monochoria-ness’. Then that passage morphs into a stream of waterlily leaves, together with the thin streaming leaves of Triglochin.

As I worked on this series of paintings some of these ideas have taken a form that seemed to have a graphic, diagrammatic quality, appropriate for printmaking methods like woodcut printing. On the left of this painting is an image I stole from Charles Darwin – a method of notation he used to describe the movement of plants. On the right-hand side I have put a linocut image of the intestine of a lamprey fish; one of many systems of flow and turbulence on which I have drawn describe this rich and fecund billabong.

Key of E major. Exuberance. Abundant fertility.

From the edge of the great flood plains of Garrangari and Garrangalli, N.T. 2012–14

watercolour, woodcut, linocut, graphite pastel, coloured crayon, 154.5 x 963 cm

On the western margins of the Gulf of Carpentaria in East Arnhem Land lie the vast flood plains of Garrangari and Garrangalli. In June 2011 I was standing on the edge of the monsoon rainforest with Djambawa Marawili, the great Yolngu leader and artist. We were looking across the plains towards pools of water from the last of the rains, and in the shimmering haze the distant shapes of huge banyan trees and ancient middens came and went. Djambawa recounted how in the dawn of creation – the ‘first morning’ – a number of ancestral figures had moved up from the coast, digging for edible roots as they went, creating springs of fresh water that still bubble out at intervals all along the plains. He described how when the first sun came up on that first morning these ancestor women turned into brolga cranes. As he sang the song he pointed towards the distant origins of the flood plain to the west, and as he gestured several brolgas emerged from the mists, as if summoned by the sweep of his hand. Groups of them flew slowly and majestically towards the sea.

This was the originary moment of this painting. For the next three years, guided by the great Dhudi-Djapu clan leader and artist Mulkun Wirrpanda, I drew and collected specimens of the plants and trees of the region – edible roots and tubers, and the various water plants of the flood plain. In the painting I have drawn various trees festooned with the many vines and their edible tubers: Ganguri (Dioscorea transversa), or long yam, and Ganay (Ipomoea graminea). And a number of plants with smaller tubers: Bulwutja, or Wapulkuma (Trichlochin dubium); Riny'tjaŋu (Eriosema chinense), with its delicious round tubers, much celebrated by the Galpu clan in ceremony; and Räkay (Eleocharis Sphacelata), or water chestnuts, which are of great nutritional and mythic importance.

For me the great miracle of that morning in the season of Midawarr rested in that moment of time – being there, seeing the living land and sensing the Deep Time so intimately linked in partnership and correspondence with the life, art and religion of the people who have lived in it for so long.

Key of C major. Relationship. Correspondence. Connection

Mallee ‘Gilgai’ - Ephemeral Pools - Wyperfeld National Park 2011

watercolour, charcoal and graphite

150 x 107

After fire - Spiny-cheeked honeyeaters at Lake Monebeong 2011

watercolour, charcoal and graphite

150 x 128

History of the Whipstick Forest with ephemeral swamps and gold bearing reefs 2011

watercolour, charcoal and graphite

234 x 287

Regeneration after Fire – The Seeders and the Sprouters 2011

watercolour, charcoal and graphite

154 x 256

Ephemeral water with New growth- Murray Sunset National Park 2012

watercolour, charcoal and graphite

230 x 325

From the edge of the great flood plains of Garangarri and Garrangali N.T 2014

watercolour, woodcut, linocut, graphite pastel, coloured crayon

154.5 x 963

Murray Sunset Refugia with Ventifacts 2008

carbonized wood, watercolour and graphite on paper

210 x 110 cms and 14 satellite ventifacts

A Natural History of Swamps III, Heron in Swamp - Loy Yang Power Station 2014

watercolour on paper

114 x 176